About the Reading:

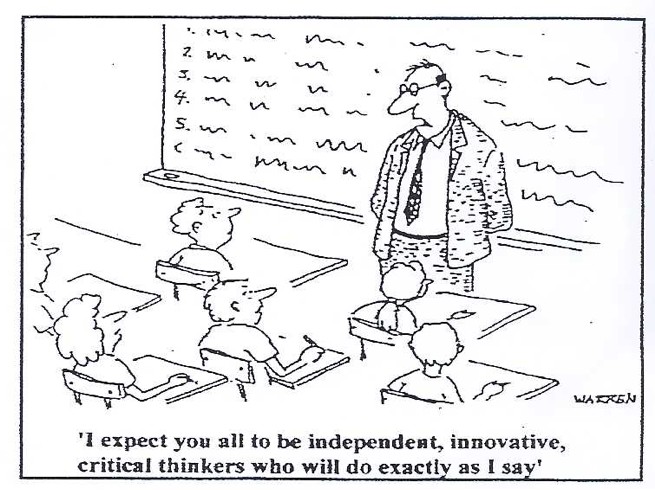

Many researchers, doctors, philosophers and scholars have tried to solve the age old problem of student disengagement and academic under-performance in the public school system. Ira Shor writes about these struggles in his book, Empowering Education. In chapter one, "Education Is Politics: An Agenda for Empowerment," Shor cites many causes for students' lack of educational success. He states that the root of the problem, though, lies in undemocratically functioning classroom settings, saying that "many students do not like the knowledge, process, or roles set out for them in class. In reaction, they drop out or withdraw into passivity or silence in the classroom." According to Shor, in far too many classrooms students view their teachers as autocratic figures and see themselves as having no role in makings of the classroom syllabi. Shor continues the chapter by reiterating this point again and again, asserting that teachers and schools need to undergo a paradigm shift. The author is fully convinced that if teachers would just open up the classroom as a free space where students feel they have some control, power and choice within their education, that we would see a massive change in the number of students actively participating and learning within schools. Furthermore, Shor believes that teachers should throw out their multiple choice tests. Get rid of rote memorization and skills based lessons, and begin to ask more questions. There should be an emphasis on process based learning, or what we may now call inquiry based learning. Students should stop and think about why they are in school, they should be taught to "question answers" rather than "answer questions." The teacher in this model of excellence is thought of as a facilitator or a coach, rather than an enforcer or knowledge depositor.

Why Shor is right...

As I was reading this text I kept flip flopping between underling words, phrases and quotes with extreme excitement and intrigue, and highlighting words, phrases and quotes with a strong sense of disagreement. I think in many ways Shor really hits the nail on the head. Students need to think about what they are learning and why they are learning it. Metacognition is an important piece of becoming a life long learner. This is why many teachers have students take the multiple intelligences test, to help them learn about the ways in which they learn best. With all of the research about ways in which students learn differently, teachers have been told to differentiate instruction. This is my fourth year teaching and I can honestly say that most of the teachers I've observed and had the fortune to work with do differentiate. Most teachers offer different ways for students to show what they know, they encourage participation and questioning. I've worked differentiation into my classroom and tried to be more of a facilitator for learning rather than an enforcer of knowledge. Throughout the school year my seventh grade students have the opportunity to complete various creative assignments, use technology, participate in debates, and incorporate as much of their own life experience into the classroom as possible.

And why he's wrong...

I was with Shor until he started arguing that students should partake in the making of the classroom syllabus. I think this is a step too far, and that this idea is a bit naive and unreasonable.The twelve year olds that come into my room can't remember to bring a pencil. How would they know how to draw up a syllabus? Never mind elementary school students. I think students need a set of parameters to function within. They need direction, guidance, and someone to oversee the activities they are engaged in. Does this mean that I should refuse to be flexible? No. Most definitely not. I think teachers need to be flexible and accommodating, but not to the point where they hand over all control to students. Shor seems to recognize this struggle when he cites a conversation from a 1930s labor workshop. One of the men involved says "No matter where this kind of educator works, the great difficulty is how to make education something which, in being serious, rigorous, methodical, and having a process, also creates happiness and joy." It's VERY difficult for students to self-monitor and function in an environment that is too open and breezy. I've tried it. Kids need some sense of routine. They need the teacher to provide them with some expectations and guidelines. As much as I wish this utopia of open-minded, free thinking and engagement existed, it does not. I think Shor could have written more about how to create a structured and rigorous environment that is simultaneously democratic. Our formerly studied authors, Delpit and Johnson would probably agree. Many students come from unstructured and disorganized homes and crave teacher authority and leadership.

Another place where my highlighter and pencil marks lit up the page was the part in which Shor said "education is more than facts and skills." Education most definitely is more than these two old school practices. It is more than lecturing and note taking. However, skills based learning has its place, again, I think Delpit would agree. Students need to practice adding without a calculator. They should memorize their times tables. Students should easily be able to find Asia on a map and point out the state in which they live. Should these facts and skills be taught all day every day? Should these facts be the center of all curriculum? Again, definitely not. But they have their place. How can a teacher expect students to work independently or in groups to complete cooperative projects without some kind of foundational knowledge? What ends up happening in this scenario is that kids form great opinions and answer great questions, but have no basic understanding of the places they are discussing. So, again I found myself disagreeing with Shor.

Final Thoughts:

In summary, I think Shor is a great writer and philosopher, but I don't think his writing is quite practical and applicable enough for the real living, breathing classroom teacher. He speaks a lot of truth, and I agree with him that many teachers (myself included) need to remember that student engagement is the key to success. But how does this play out in real life? How do you get teenagers to stop being self focused and become curious about learning? How do you have twelve year olds set up a syllabus? How do you allow students to work in cooperative groups without a basic set of facts? Also, how does this look in a classroom where a predetermined scope and sequence has been laid out? Shor raises many wonderful points, but leaves us with far too many unanswered questions.

Brittany,

ReplyDeleteI agree with most of your assessment of Shor's piece. In fact, as I read the chapter I had the same questions: how can kids who need and crave structure, along with the skills and content that form the foundations of literacy (ie literacy of all genre, math et al) be asked to co-partner curricula? My answer was that while the teacher, the content expert, controls the guidance of a class, engaged learning that begins with inquiry and ends with a product, can be considered as a type of co-writing a curriculum. What can that look like for younger students? Maybe in a science class with a curriculum written around eco-systems, the teacher can guide the students towards reading background information on the subject before they are guided into asking questions about a certain eco-system they want to investigate. They then research their own answers while being encouraged to make notes about more questions they are asking during their research, and then sharing their answers via a presentation to the class: hence, they are co-writing in a way, the curriculum the class is learning. So, my answer came in less a literal way than I originally thought. Co-writing the curricula can also come via project-based inquiry learning so that they are gathering information that might normally be taught, while trying to create a new product or solve a problem. The structure part students need can come with the students helping to set up the classroom for best effort and vote on time-limits etc for projects (within reason of course as we all have timelines etc. to which we must adhere ;) )

Thanks, Polly. I do think that student choice and involvement are important. I think the idea of having kids pose their own questions and look for the answers is a good one, but even with this, students have a hard time. Maybe it's just the age group I'm dealing with, or the fact that the kids have been spoon fed since kindergarten, but it's very challenging to have them think about things in an abstract manner. It's also incredibly time consuming. Like I said in my post, I go back and forth with much of the material Shor writes about. I think it's all wonderful in theory, but feel that it's much easier said than done. I also think that it's one thing to have students design a project and complete said project, but it's a whole other ball game to have this take root in every day lesson planning. I'm not at all opposed to allowing more student control and choice, but just haven't found an efficient or meaningful way to incorporate these ideals into daily lesson planning. I appreciate the examples and feedback you supplied, I hope I don't come off as unaccepting of your advice :)

DeleteLove the dialogue between you and Polly above... in fact, I want to resist reiterating just because "I am the teacher" and say instead that these are real questions I hope to discuss on Wednesday night :)

ReplyDeleteWhat we are really talking about is that all students are different and all teachers are different. There is no such thing as all sizes fit. I have an unrealistic impossible approach to all of this.... Go through the entire roster and pick your team that fits your personality. It really is not a new approach....It is called a cohort. Think about our group. We have great interactions yet we come from very diverse backgrounds.

ReplyDelete